Anhidrosis

Did you know that aside from primates, horses are one of the only mammals that sweat in the same way humans do to help regulate their body temperature? In fact temperature control in horses needs to be even more effective, due to their large mass and relatively smaller surface area.

Unfortunately a small proportion of horses lose their ability to sweat, a condition referred to as Anhidrosis.

Anhidrosis in horses can be described as the inability or reduced capacity to sweat. The word Anhidrosis comes from the Greek word hidrosis, which means “sweating”. The prefix an means “not”. So anhidrosis literally translates as “not sweating”. It can pose serious problems for your horse in the hot weather. If it isn’t recognized and treated quickly, potentially fatal heat stroke can result.

Horses suffering this condition may also commonly be referred to as ‘non-sweaters’, ‘dry coated’ or ‘puffers’. This ability to sweat allows your animal to maintain their interior core temperature at such a point so as not to interfere with their enzyme driven metabolic processes which are also of an essential nature. A horse with anhidrosis body temperature will continue to rise because it can’t produce sweat.

In horses it’s a big problem with performance ability, because a lot of the thermo-regulation, or the ability to regulate body temperature during exercise, is through sweating. Not being able to sweat leads to overheating and therefore an inability to perform.

The condition was first documented in the 1920s with early research stimulated by problems that arose when the British moved their sport horses to colonies such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and India. They were surprised to find that a number of their runners and polo horses ceased sweating when they were transported to a hot, humid climate.

The condition is not fully understood, and there is no proven consensus on what causes it, as well as no veterinary cure. However I have successfully treated horses with this condition and seen them return to sweating again with Equine Bowen Therapy. But let’s first learn more about this frustrating disease.

It is seen most often in hot and humid regions, such as the Gulf states in the USA, Asia, parts of Australia and also here in the Middle East. Often horses will sweat normally when the climate is cooler, but with the onset of the hotter, humid weather the problem occurs, or if horses are travelled from a cooler climate into warmer more humid locations. It occurs more commonly in horses that are transported into hot and humid areas compared to horses native to these areas. Crucially it appears it is not heat alone that triggers it, but rather heat combined with high humidity. It is most often associated with periods when the night-time temperature does not go below 80o F (27o C). If overnight temperatures and humidity levels remain elevated through the night, it doesn’t allow the horse to gain any respite from the heat, causing his system to be under constant stress. It has been estimated that 20-30% of the horses in hot, humid areas suffer from anhidrosis to some degree. However, it must be noted it has been observed on occasion in dry arid environments.

It can effect all breeds, ages and types of horses, although it appears some breeds are disproportionately effected. A study has indicated that anhidrosis is most common in thoroughbreds, quarter horses and warmbloods and mostly occurred in horses in training. The odds of anhidrosis have been reported to be 21.67 times higher in horses with a family history of anhidrosis, highlighting the strong genetic component to this disease (Johnson, 2010). Anecdotally we have observed certain bloodlines seem to be more prone to the condition in thoroughbred horseracing. Anecdotal reports also reveal that dark coloured horses are affected more frequently than light horses.

There is another twist to the affliction. Even non-exercising horses can be anhidrotic. This fact came to light several years ago when a survey was conducted by the University of Florida to determine the extent of anhidrosis in the area. Involved in the study were 834 horses residing on four different Central Florida Thoroughbred farms. Of that total number, 91 horses were in training. It was found that 23 of those 91 horses (25%) were anhidrotic to some degree.

The next-highest category for the affliction was that designated as non-pregnant mares. This category included mares which had foals at side and those which did not. There were 74 mares in this category, and 11 of them (15%) were anhidrotic.

There were 217 pregnant mares in the study group, and only nine (4%) of them were anhidrotic.

Showing even less of a problem with anhidrosis was the adolescent group, which included 401 animals ranging in age from foals to colts and fillies which had not begun training or had not been bred. Of that group, only six (2%) were anhidrotic.

Eighteen stallions were included in the survey, and two of them (11%) were anhidrotic.

Symptoms

Usually it is first suspected from observation of the horse and lack of sweating during training. Just like humans some horses sweat more excessively than others, but when a horse appears to hardly be sweating at all then alarms bells will ring. Non sweaters may still have a minimal amount of perspiration under the jaw, along the neck, at the base of the ears, between the hind legs, and under the saddle but it’s not the typical sweating patterns. Some will show some sweating behaviours; it’s just not enough to regulate the body temperature. The fact that most horses still sweat to some degree can confuse owners who assume that Anhidrosis is a complete lack of sweating. Only n extreme cases, the horses will altogether lose their ability to sweat; that’s why they also call the condition dry-coat, or dry horses. They never sweat at all.

In some horses, the reduced ability to sweat develops gradually but in other horses, the change is rapid. About half of affected horses show a typical sequence of events over the course of a few to several days. It is first characterized by profuse sweating (more sweat, longer lasting than usual), followed by less and patchy sweating, and finally a complete or nearly complete absence of sweating.

They will also pant vigorously when hot, with flaring nostrils. Horse’s sides heave as they take rapid, shallow breaths in an effort to lose body heat. They breath harder than you would expect for the amount of work they do, and continue to do so long after exercise stops. They may even breathe hard when at rest on a hot day as they tries to compensate for their failure to sweat.

If in a paddock they will stand in a shady area or water if there is a pond or stream to try to get some relief. In the stable they will find the coolest area and lie down. Their core body temperature may remain elevated, and both their heart rate and blood pressure may also be above normal. There will be signs of dehydration as detected with the “pinch test”. Rectal temperature will be over 38 degrees Celsius. Affected horses will show signs of fatigue and lethargy, and may seem depressed and be reluctant to work, becoming exhausted quickly.

There may be a loss of appetite or reduction in water consumption, and loss in body condition.

Horses with a persistent case of anhidrosis eventually will show external signs. The skin will become dry and flaky and hair will fall out, particularly around the face. Dry coats and hair loss result when oils produced by the sebaceous glands are not taken to the skin’s surface by sweat. As the skin becomes dry, it also might become itchy. The dryness problem can be alleviated to some extent by applying oil rinses after cooling the animal with water.

Causes

We still don’t have a definitive answer to what causes some horses to suffer from this condition, whilst others in the same environment cope just fine. But there are several theories.

First we must understand a little about the sweating process in the horse’s body.

During exercise, muscles generate heat; heat is a by-product of energy metabolism.

Circulating blood absorbs heat from the muscles and carries it off to the lungs, where some of the heat dissipates when the horse exhales, and to the skin, where heat can radiate out from the horse’s body. Breathing accounts for approximately 25 percent of a horse’s ability to control their internal temperature but sweating is a horse’s primary mechanism for cooling and can account for up to 70-75 percent of a horse’s ability to cool itself off. Looking at thermo-regulation in general, sweating is the most efficient way a horse can moderate its body temperature.

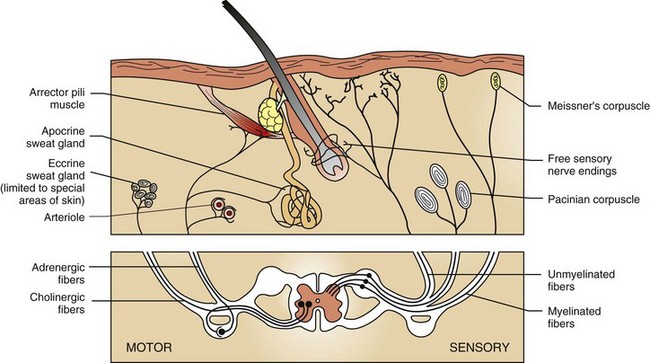

During periods of intense activity, heat production can increase by as much as 50 times. The average temperature of a horse at rest is 37 to 38 degrees celcius, but this can rapidly climb to 40 to 42 degrees C when undergoing exercise. If the horse produces more heat than he can unload through breathing and radiant cooling, his core temperature begins to rise from its normal resting temperature. A part of the horse’s brain called the hypothalamus (which, along with many other jobs, acts as his central thermostat) senses the increase. It sends signals rushing out to sweat glands distributed in his skin. The sweat glands begin to pump out sweat. The sweat produced has a number of components, including proteins, electrolytes and significant amounts of water. The proteins found in sweat are primarily glycoproteins, surfactants and proteins associated with skin defence. Electrolytes (including sodium, potassium, and chloride) are found at a higher concentration than blood, particularly potassium. A horse’s sweat has a higher concentration of electrolytes than yours. As the sweat evaporates, it carries heat away from the skin, reducing the horse’s body temperature.

If the heat is not dissipated and temperature increases beyond 41 C this can be very dangerous, leading to stroke, brain damage, heart attack and death.

The harder the horse works (or the hotter the weather), the more he sweats. He can produce more than twice as much sweat as you can per square inch of skin. During intense exercise (cross-country, polo, endurance racing) he can lose 10 to 15 litres of fluid in an hour through sweat and through water vapour that he exhales with each breath. The loss depends on climate conditions as well as exercise levels, and it can happen even if you don’t see sweat pouring off your horse. On a hot, dry day, sweat may evaporate almost as quickly as it forms; he may lose a large amount of fluid without your being aware of it.

Horse’s sweat glands are densely packed in horse skin (810 glands per cm2), primarily exiting to the skin surface at a hair follicle. These tubular, coiled glands have a rich blood supply and numerous nerves are found in close proximity to the glands.

The sweat glands are highly innervated and are stimulated by the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight response). Under ordinary circumstances, sweat glands produce perspiration in horses when triggered by hormones after they are prompted by the body’s adrenal glands. The sweat glands are equipped with beta 2 receptors, and when stimulated, cause the glands to react and the horse to perspire. One stimulus for the sweat glands is epinephrine in the bloodstream. Another form of stimulus is believed to be transmitted via the nerves.

Epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) is a hormone and neurotransmitter that stimulates the beta-2 receptors in sweat glands to release sweat. Epinephrine (adrenaline) is a stress hormone. When stress levels are elevated by extreme heat and humidity, there are elevated levels of epinephrine/adrenaline in the horses blood steam. This in turn causes a down-regulation or de-sensitization of the beta receptors on the sweat glands. They become overstimulated and start to shut down and reduce or cease sweat production. The body is a very complex system constantly working to achieve homeostasis, and when one element becomes out of balance it has a knock on effect on the whole system, in this case effecting adrenal glands, endocrine glands and the neuromuscular system causing them to be overly sensitized to adrenaline.

There is a relationship between sweat and stress. A stressed horse will sweat, in the same way as humans. Stress can come from the environment, diet, or coping mechanisms of the horse. Horses will produce more sweat during transportation in vehicles or aircraft, and at the start of a race or other performance. A pivotal component is the horse’s overall stress load; which can affect how he copes with the unchangeable environmental difficulties. It’s believed anhidrosis horses are under some form of constant stress. These stress hormones are normally released in fight/flight events or in the case of other major stress events. For example if the horse is already stressed from shipping, a heavy training or competition schedule, being broken in as a young horse, a commercial processed diet, lack of turn out or socialisation, respiratory infection or chronic discomfort from pain from an injury, the body is already in stress-response mode and levels of Epinephrine are elevated to begin with. He is overwhelmed trying to deal with shipping, digestion, pain and the last thing his body can handle: the weather. If the horse is not sweating properly, this will cause the horse further distress, resulting in abnormal behaviour and exacerbating the problem.

Stress will also deplete the hormone dopamine causing an imbalance of dopamine to the nor-adrenaline/adrenaline complex. Dopamine is used first by the brain, then by the cardiovascular system and last by the sweating system. If the horse is not producing enough dopamine to satisfy the needs of the brain, the cardiovascular system, and the sweat glands, sweating loses out to the needs of the brain and cardiovascular systems. A reduction in dopamine below a certain level allows the well-known vasoconstrictive properties of the nor-adrenaline/adrenaline complex to predominate and reduce the blood carrying capacity of the peripheral vascular system to a minimum, thereby reducing the ability of the sweat glands to function properly.

It is also felt that the condition is further aggravated because the animal’s hair follicles eventually become plugged with dried sebum.

When the horse gets into cooler weather, the receptors will up-regulate, and the horse will sweat again. Once the sweat system is stabilized the physical component of stress is removed, so removing the cause of the distress.

Prevention

The best prevention is awareness of the horse’s physical condition and the contributing components of anhidrosis. Recognizing when a horse is in danger of heat stroke and subsequently restraining the horse from further physical exertion may prevent the development of anhidrosis.

Riding and exercising your horse during the coolest part of the day and keeping him out of the sun are simple, but effective, solutions. Exercise him early in the morning or in the evening, when it’s not so hot. Dampen the coat with water before starting exercise. Take frequent breaks, allowing his breathing to recover before you ask for more effort. Exercising during periods of high heat and humidity should not be routine.

Cool him out aggressively after work with cold water and fans. Monitor his vital signs, and don’t stop your efforts until they’re normal.

Taking the horse’s rectal temperature and maintaining a temperature under 103.5 degrees is important. If the temperature goes higher, you should immediately take steps to cool the horse down by sponging or bathing his head, neck, and legs in cool water to return the horse’s temperature to normal. As the horse cools down, his respiratory and heart rates will return to normal.

Try to get horses fit before the hotter months of the year. Starting to condition the horse once the temperature is already high may predispose horses to anhidrosis. Some anhidrotic horses may only be able to compete during the winter months and may need to be rested during summer.

When bringing your horse to a hot, humid climate, allow him to acclimate with 10-14 days of turnout and light work before returning to regular training and showing.

A readily available supply of cool drinking water is extremely important so that there is a constant supply of moisture to be converted into perspiration. Some horses like to stand in water for the cooling effect it has on their systems.

Try to provide a cool environment for the horse. Air conditioned stables are ideal, otherwise high gabled stables with ceiling fans or ridge top roof vents will also help to improve airflow. In the stable, fans and misters may be used to circulate and cool the air. While high humidity cuts into the evaporation process, the misting fans can lower barn or stable temperature. Studies at Louisiana State have revealed that a misting fan can lower ambient temperature by as much as 15 degrees.

Night-time turnout is helpful because there is more air movement and temperatures can be cooler than in stalls.

Body clipping the horse, if practical, will allow more air close to the skin and help keep the horse’s temperature down. Regular grooming stimulates blood flow, bringing essential nutrients to the skin and sweat glands.

Worming and vaccinations can place additional stress on the horses systems, so making sure that horses are healthy and up-to-date on these going into the hot, humid season will help prevent development of anhidrosis.

Address any body discomfort, hoof balance, sore muscles, gastrointestinal imbalances which would cause additional stress.

In some cases, horses may need to be moved to a cooler climate if at all possible.

Nutritional Support

A number of studies have shown that horses with anhidrosis have reduced levels of electrolytes in their blood. As horses use and lose electrolytes in sweat, electrolyte supplementation in the diet is helpful in resolving the condition for some horses. Sodium, potassium and chloride are the electrolytes that are lost during normal sweating in the horse. Anhidrotic horses often begin to sweat after treatment with sodium and potassium chloride.

Feed a daily electrolyte supplement designed for horses in hot, humid conditions e.g. Humidimix. It has been reported that some horses with a history of anhidrosis that improves during the winter do much better if they are supplemented with electrolytes before the onset of hot weather. Some horses have managed to train and race without a relapse. Therefore, do not wait for the problem to return before you start feeding electrolytes.

Fermentation of fibrous feeds and protein in the large intestine leads to the generation of extra heat within the body. Avoid high protein diets during hot conditions. It is critical to feed neutral or cooling ingredients: grass hay or irrigated grass (if your horse is not metabolic), rolled barley, soaked beet pulp, hemp oil, chia seed, and small amounts of alfalfa. Oats are the most fibrous grain fed to horses, and this can be replaced with lower heat-producing grains such as rolled barley, corn or vegetable oil. Half a litre of corn or ¾ litre of rolled barley or ⅔ cup (175ml) of vegetable oil will provide as much energy as 1 litre of oats.

Steaming hay: 1. increases its water content and can help to reduce the risk of impaction colic. 2. prevents loss of electrolytes that can occur with soaking hay. 3. will kill mold spores reducing the risk of colic and respiratory problems.

Numerous anecdotal remedies have been employed to help horses with anhidrosis. Some feed supplements are available that appear to have a positive effect on anhidrotic horses but there have been no controlled studies to prove their efficacy.

There are many commercial products available (One AC®, True Sweat®, or Platinum Refresh®) but they have limited success.

Some research has shown that One AC can provide the necessary raw materials to reverse anhidrosis when used properly with horses which have been taken out of training for about three weeks, to allow the system to respond to the supplement.

One AC is based on the theory of imbalance of dopamine to the nor-adrenaline/adrenaline complex with its ingredients: L-Tyrosine, Choline Bitartrate, Niacin, Pyrodoxine HCL and d-Calcium Pantothenate. Horses given this feed supplement may begin sweating again within 10 to 14 days.

Antioxidants, such as vitamin E, have been documented to be an effective treatment in some horses with anhidrosis. When a horse is unable to sweat, oxidative damage likely increases due to the high environmental heat stress the horse encounters. Therefore natural antioxidants, such as vitamin E and vitamin C, may be helpful in limiting the damaging effects of free radicals and other products of cellular oxidation. Natural-source vitamin E is superior to synthetic sources.

Food supplements containing L-tyrosine have also been shown to help horses maintain healthy sweating reactions. A variety of B vitamins help to support normal cellular function in anhidrotic horses.

Arginine, an amino acid, is an important nutrient in the formation of nitric oxide synthase. In the horse, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) may promote peripheral vasodilation. An isoform of eNOS, neural constituent NOS (ncNOS) helps to regulate neurotransmission in the central and peripheral nervous system. Both forms of NOS are postulated to play an important role in the physiological control of sweating in the horse. Arginine is a precursor to nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and thus may play a role promoting blood flow in these pathways.

It has been suggested that anhidrosis is related to poor thyroid function. One study suggested a possible connection to thyroid function due to possible iodine deficiency. Although this link has not been proven, some success with iodine supplementation has been reported, but the researchers cautioned that—if supplementing iodine or thyroid hormone appears to result in a renewed ability to sweat—this shouldn’t be taken as proof that hypothyroidism was the cause.

An old Cajun trick that some claim is effective is adding beer (containing yeast extracts and B-vitamins that are helpful in sweat gland function), to the horse’s feed. The darker the brew, the better!

Clenbuterol (which must be administered by a vet) can have some success.

When tested in controlled research settings none of these approaches have proven effective. However, in consultation with your veterinarian these anecdotal treatments might be worth trying.

Treatment

If anhidrotic horses are treated early, it may prevent long-term structural damage of the sweat glands. If it’s not treated in a timely matter, permanent cellular changes may result. In chronic anhidrosis cases, sweat glands ultimately atrophy.

Once a horse develops anhidrosis, accommodations must be made to promote good health and vitality. Changes will need to be made in the environment, the amount and type of exercise, and the diet.

There are several ways to assist your horse if he has Anhidrosis. The best solution would be to move it to a more temperate climate, at least during the humid months. This helps the horse manage high body temperatures immediately; many horses start sweating again once in a cooler environment. However obviously this is just not possible for many people. So most of the options available are purely preventative or dietary and have been listed above. There is no proven cure for anhidrosis.

However there has been success treating horses with acupuncture and Equine Bowen Therapy.

How Equine Bowen Therapy can help

Anhidrosis in horses is a complex combination of neuromuscular and hormonal imbalances. The over riding stimulus seems to be stress. The stress response is regulated by the autonomic nervous system, which is divided into two parts, the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions typically function in opposition to each other. The sympathetic system relates to your fight or flight state, and is activated when in a life threatening or stressful situation. The parasympathetic system is the rest, relax and digest state. It is in this state that the bodies healing and repairing takes place.

When a horse has anhidrosis he is stuck in a sympathetic state, over producing the stress hormone epinephrine/adrenaline. Equine Bowen Therapy stimulates the body to switch back into the parasympathetic state, reducing the production of stress hormones. Reduction in epinephrine/adrenaline allows the receptors in the sweat glands to reactivate and the horse can begin to sweat again. By moving back into the parasympathetic state, the horses well being will improve and he will feel more relaxed and calm.

Another component in the elevation of stress hormones in anhidrotic horses can be underlying injuries causing pain and discomfort. Equine Bowen Therapy relieves muscle spasm and tension, reduces inflammation, speeds up healing and reduces pain. By switching the horse’s body into the parasympathetic state the horse’s body can begin to heal itself. So when underlying health issues are addressed, stress hormone levels will drop and again the receptors in the sweat glands will begin to function normally once again.

In addition, a horse that has been suffering form anhidrosis will have been breathing heavily, or ‘panting/puffing’ in order to cool themselves down. This will put a large amount of strain and tension on the diaphragm, intercostal and abdominal muscles. Equine Bowen Therapy has procedures and moves to release tension within the diaphragm and the surrounding muscles affected by the respiratory system.

In summary, anhidrosis occurs when the horses body has an imbalance in his homeostatic systems. Equine Bowen Therapy is an excellent way to bring the horse’s body back into a balanced and healthy state, and effects are usually within 3 to 4 treatments, with maintenance sessions required on a monthly or bi monthly basis as long as high temperatures and humidity persist.

Case Study

Mujaazef is a 13 year old thoroughbred former racehorse, now retraining as a riding horse and showjumper. When I took his history before his first treatment I learnt that he was anhidrotic since he had arrived from his racing stable after retirement. He was completely dry coated and did not sweat at all, would pant heavily in hot weather and the skin on his face was dry, scaly and without hair. His coat overall was dry and in bad condition, without any shine. He looked older than his years and wasn’t very happy. He could not be ridden in the summer at all, and early morning turn out was limited, as even when hosed down prior to turn out he would be very uncomfortable. He lived in an air conditioned stable but this still wasn’t sufficient to manage his condition.

As well as the anhidrosis, he had stiffness in his hindquarters when ridden. He would feel tight and braced in is back, and would take a little while to warm up. He was tighter when moving on the left rein. When jumping he lacked collection. His rider felt there could definitely be improvement in his gaits and that he needed to swing through his back more.

When I examined him before his first session, we trotted him up and I palpated him. Had muscular tension throughout his back and hindquarters.

I treated him on a weekly basis for the next 4 weeks. He was a busy horse in the stable, and showed limited responses whilst treatment was given, although he didn’t object to the therapy either. After the third session his groom and rider reported that he had started to have small areas of sweat when he was on the walker, under the mane, between the legs, and under the belly. On the 4th session as I was working he began sweating profusely, on his neck, chest, under his belly and between his hind legs. This despite being in an air conditioned stable and being dry when we began. He was calm and relaxed, and he continued to sweat for the remainder of the session.

Since that treatment he continued to sweat normally, in fact he would sweat more than some of his stable mates when out working. He could begin to be exercised again, and took part in jumping competitions in the competition season. His coat bloomed, and the hair grew back on the bald parts of his face. The dry scaliness disappeared, and he put on condition and even got a little fat! His temperament changed, and he became happier and expressed himself more and enjoyed his training. His muscular skeletal issues were resolved and he no longer had pain and tension when palpated and his rider reported that he felt much looser and freer in his paces.

After that 4th session when he began to sweat again we began to space his treatments out further, until I saw him on a monthly basis for the duration of the summer, and as the weather cooled down he was treated bi-monthly. In the winter the results held and he was not treated for several months, until the weather began to heat up again in the spring.

Testimonial

Gen started treating Mujaazef with Bowen Therapy when the temperatures started to increase in spring 2019, we noticed that he wasn’t sweating and would pant heavily when being ridden especially when it was humid. The condition of his coat had decreased, he had lost some hair on his face and was experiencing some muscle stiffness and tightness when ridden. Previous to Bowen we had tried other remedies for Anhidrosis which were unsuccessful, thankfully within a few sessions from Gen Mujaazef had begun to sweat much more freely, his coat had started to improve, ridden work had improved due to more freedom in his muscles and he was in general much happier and would call out when he knew it was time to be ridden.

We continued with Bowen Therapy throughout the summer and then as temperatures decreased we started to spread out the sessions, we had some other horses receiving treatment so Gen would take the time to check him each time she came. He would hold the benefits of each treatment well and felt like a different horse to ride, he used to feel quite one sided which could be felt on smaller circles which can be the norm for an ex-racehorse but gradually he became more even, he gained even more freedom behind and became lighter on his forehand which in turn helped to improve his lateral work and jumping. The past season he was nicely jumping through combinations which he used to struggle with.

Gen has increased the frequency of treatments as the humidity has increased and he has stayed in very good condition through this summer as he is coping with heat much better.

Very informative. My horse has this condition. Do you know if there are any practices which deliver this therapy in Bahrain?

Hi Helen, thanks for the comment. I’m not aware of any other Equine Bowen practitioners besides me in the Middle East unfortunately, but I have read of good results treating Anhidrosis with acupuncture as well, so it may be worth checking to see if there is an equine acupuncturist in Bahrain. I would love to come over if there was enough demand there, but I haven’t got around to promoting myself in Bahrain at all so far. Hope you can resolve this problem for your horse soon.